Celia Mancini

"Go Well, Celia" was a tribute to the short amount of time I spent with Flying Nun musician Celia Mancini that was originally posted to my blog after her death in September 2017; shortly afterwards, it was syndicated online via The Pantograph Punch and the Dunedin student magazine Critic, which also put it in print. A few weeks later, Chris Heazlewood, Celia Mancini's King Loser bandmate and lifelong friend, read out the final paragraph on Radio New Zealand during a composed tribute to his bandmate.

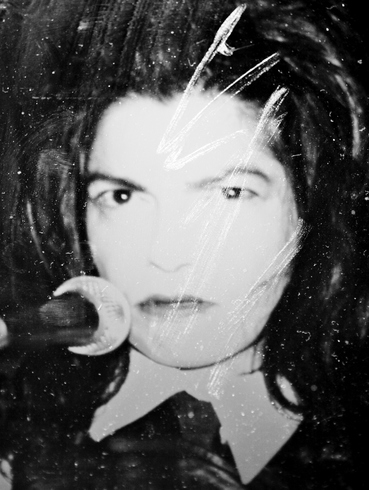

The first time I saw Celia Mancini was on celluloid.

Three years ago, my flatmates and I headed out in the rain to catch a screening of Margaret Gordon’s documentary about the Christchurch band Into the Void at Alice’s, a theatre in the centre of town that holds about 30 people.

Most of the documentary consisted of the band laughing about how they drank together far more often than they made music.

But the atmosphere changed when a clip from King Loser’s '’76 Come Back Special' video jumped off the screen. A presence appeared: a femme fatale with jet black hair and red lips. She sprinted in short heels through the streets of Auckland, picking off men with whatever she had lying around: a car, a rifle, a karate chop.

“Wow,” I breathed.

One of the people she murdered in the video was her bandmate Chris Heazlewood. Their personalities sparked when they met in April 1992. Celia spat venom, and Chris liked it. Celia liked him, too. King Loser was born shortly afterwards.

“That whole video was all her idea!” he cried. “She’s got a real good eye for iconography. She was like, ‘I need to be in a black vinyl catsuit, and I need to be killing everybody, and I need to die at the end.’”

Celia was larger than life. She was also still very much alive. Unlike the actual members of Into the Void, who were somewhat useless at remembering the finer details of their history, Celia had scrapbooks full of newspaper clippings. More than 20 years after the fact, she still had everything saved, as if she always knew that someone would need it one day. She was both a rock star and an archivist. My heart glowed. As disparate as our lives seemed, I could relate to her in that one small way.

Media is often talked about as if it is some evil, homogenous lump of globalised ephemera with no real connection to anything or anyone other than capitalism and corporate profits. But in New Zealand, people step out of celluloid and cross over from the screen into everyday life all the time. You just have to know where to look, and who to find.

At one point in the documentary, Into the Void played in a gravel lot on High Street where their practise room used to be. One kid watched from the sidewalk, his hair bouncing. An hour after the screening, Mary and I were at the Darkroom, and so was he.

“We just saw your movie,” we crooned. “Loved your scene.” *

Though Celia first became known for her presence in Christchurch bands like The Stepford 5 and The Axel Grinders in the 80s, she didn’t live in Christchurch anymore. And although King Loser was born in Auckland, the band also lived in Dunedin for a bit. Part of that history included joining Peter Gutteridge in a reformed line-up of Snapper. The New Zealand poet David Merritt once referred to their triumvirate as “an axis of good and evil”.

Celia’s and my paths first crossed two years ago in a bar on Karangahape Road in Auckland. Though I had killed a lot of time on K Road – I had written a novel there in another life, years before moving to the South Island – I had never seen Celia before. This time around, I was doing an oral history project on Gutteridge. This time, I knew who I was looking for.

Chris Heazlewood was playing at the Audio Foundation, though I missed it (what gig finishes by ten?). Apparently, Celia turned up unannounced with a drummer and demanded that they play. Chris conceded. They smashed it.

After the show I ended up at Verona, and Celia was there too, in a black silk dress. Her arm was in a cast. One of her front teeth was chipped. The bar was loud and crowded. She talked with a drawl, and a bit under her breath. Her words rolled together like liquid and I couldn’t make out a thing she said. After a few moments she held up her cigarette and announced: “I’ll leave you for more conversation with this one.” She nodded to me. “Scintillating.” That I understood. I broke into a smile. I had just been insulted, but I didn’t care. She was funny.

Later that night, a boy at the bar leaned in my face when he heard I was writing about Peter Gutteridge.

“Who?” the boy spat.

“He’s a musician,” I replied.

“Who?” he asked again, louder.

“Uh…” I tried to think of which band to mention first.

“I know who he is,” the boy seethed. “He was a friend of mine. Do you think he would have wanted you to write about him?”

He hit a nerve. I almost cried.

Celia wasn’t like that at all upon learning I wanted to write about Peter.

“I have no questions to ask you,” she said. “I’m just grateful.” She championed the project to several of their mutual friends, and put me in touch with all of them.

We did her oral history on a sunny winter day in Auckland in 2015. Celia didn’t have a permanent address, so we met at her friend’s flat in Grey Lynn.

Celia wanted food: she requested a pizza with anchovies, capers, and olives. I had a rockmelon. “Bring both if you can,” Celia said. Before I left, she doubled down. “I’m not joking about the rockmelon. I am half Indian, you know.”

When I arrived, Celia was waiting in the backyard.

“Hi!” I said as I approached. “I’m Hannah.”

She smiled slow. “I know.”

I had brought along the rockmelon, but by that point it had been long forgotten.

Oral histories ought to be recorded somewhere quiet, but Celia wanted to go find some sun.

“Lindsay, we need your keys,” Celia announced to her friend. “Hannah’s going to borrow your car.” It came off a bit abrupt, but Lindsay didn’t seem to mind. He tossed me his keys. I also needed power; he handed me eight rechargeable batteries and told me to keep them.

Boxes of Celia’s archives formed towers around Lindsay’s toilet. Even though she didn’t have a home, she hadn’t lost them. Her friends seemed unusually patient and generous.

As I drove, Celia drank. We ended up on a park bench near the lake in Western Springs, where ducks were basking in the late afternoon sun.

Celia poured whiskey into a mug from her flask. “Would you like a drink, darling?” She doled out the word darling like candy.

“I would, but I can’t,” I protested. “I drove us here. I need to drive us home!”

Celia’s mind moved a mile a minute. As she talked, her words started to blur again, and I struggled to separate them, just like at the bar. My replies were flat. Most of the time I managed only a generic response once she had finished. “Oh. Hm.” I wondered if she was making any sense.

Later, when I listened back and slowed down the recording, Celia was totally lucid, and I sounded like an idiot. She would go off on three separate tangents in the middle of a sentence – but at the end of every sentence, she offered up about seven ideas.

Much of what Celia said blasted apart the two-dimensional statements that have been repeated so many times about rock music in New Zealand that they are often passed off as truisms. One is that the scene is full of amateurs who learned by the seat of their pants.

Celia didn’t subscribe to any of that bullshit. She loved classical music, played ragtime and honky-tonk on the piano from the age of five, and was a brass player in several orchestras as a kid.

Another one of the two-dimensional truisms was that being on stage came with no pretence. Everyone wore street clothes and stared down at their amps.

Celia didn’t give a fuck about precedents. The world was her stage, and she was going to own it.

“People turned their back on the audience,” Roy Colbert told me over coffee. “Then, here comes Celia walking the stage like it’s a runway in a nightie. People had never seen anything like it before. Jaws were on the floor.” Roy laughed.

“I’m a bit confused lately because I don’t live in Auckland,” Celia said. “I really want to be going home. I’ve been trying for two years.”

“Where’s home?” I asked.

She looked as me as if I was blind. “Dunedin!” she cried. “Always.”

Although our first encounter was a bit acerbic, Celia treated me like gold ever since I wrote about Peter. She said my dissertation rendered her speechless. A rarity, one of her friends mused. Don’t worry, another chimed in. I’m sure it’ll wear off soon.

Celia and I reminisced about Peter and purred.

“I miss his tone of voice,” she said.

“So gentle,” I agreed.

She smiled. “So sweet.”

About a year later, word spread that King Loser had started to play together again. Shows were scheduled across the islands for that September. As the dates neared, rumours rumbled through Dunedin that communication in the band had started to break down. There was talk the band might not make it.

But they did—curiosity regarding their arrival turned into cries of lament from Port Chalmers that Celia had demanded the entire stage be moved at the last minute.

Danny and Nikolai of Elan Vital had been drinking at Mou Very to mourn its last day before being sold; a brief sojourn to pick them along the way turned into a two-hour detour.

“Have shots with us,” they pressed.

“I’ll have a beer; I can’t have shots though,” I said. “I really want us to make this show.”

After a brief detour to Chicks Hotel to drop off two bar stools and another few acquired bits and pieces, we walked the cobblestone street down to The Tunnel, where a gentle murmur floated in the air. That night outside the hotel, the atmosphere was giddy. Nikolai leapt at Danny and pulled down his pants. Renee was draped over the fence outside the hotel in a fur coat, eyes glistening and grin demented. King Loser was back.

Chris Heazlewood passed us on the street on the way in.

I lit up. “You made it!”

“Agh,” he muttered. “Dragged that bitch all the way from the top of the North Island to the bottom of the South...”

I smiled. “Well, we’re glad you did.”

The bar was packed. There were black leather miniskirts that looked like they had been dusted off from 20 years back.

There was no sign of Celia. Sometime after midnight, the band started to play without her. Eventually Celia stalked in an oversized fur coat from stage right. Her hair was teased and piled up a mile high over a white collared shirt buttoned up to her neck and a black silk tie. Celia threw her coat behind her over a lamp. Their drummer—Lance Strickland, aka Tribal Thunder—carefully removed it.

Once they started playing, it all came together. Chris and Celia taunted one another. Lance was on point. At one point Celia almost knocked the keyboard into the audience, but Lance leapt out and caught it. Elan Vital and Death and the Maiden threw themselves into each other in front of the band, manic.

“I love you Celia!” Renee crowed.

“Another whiskey, please, somebody?” Celia posited to the audience.

“Somebody get her a whiskey!” Renee hollered, lifting the decibel of the request over to the bar.

“Thought she wasn’t going to make it for a minute there,” I mused to Roy Colbert, who happened to be standing in front of me.

“Don’t be fooled,” he said. “Celia wanted all eyes on her. She loved it.”

Word of King Loser quieted down a bit again after the shows. The following summer I moved to North East Valley, and not long after that I cycled past Chris Heazlewood walking a dog along North Road.

“King Loser is playing at the Crown this Sunday afternoon,” Chris said. “So, Celia’s down obviously.”

The cover charge was only five dollars. My whole flat came; the ones with a bit of extra money covering those who couldn’t afford it.

By the time I arrived, Connie Benson was on her last song. Afterwards, King Loser were even tighter than before. There was no false starts, no long wait. The first song came like a bullet train. Wham! Celia introduced another. Wham! Then another came straight after, without any introduction. Wham!

“Shall we have Connie Benson come up and play our last song with us?” Celia asked before the set ended.

The crowd cheered. Connie’s eyes widened.

“Come on, Connie.” Celia started a chant. “Connie! Connie!”

Connie slowly took her guitar out of the case.

Connie glanced between Celia and Chris as the band launched into a riff. She watched Chris’ fingers and slowly started to imitate them. Lance lifted his chin at Connie, encouraging her to go faster.

Celia stopped the song after about 30 seconds. “All right, Connie,” Celia insisted until the beast ground to a halt, "it’s E, F#, A...” Celia rattled off the notes they were playing.

I melted for the girl for being put on the spot to play a song that she didn’t know. Connie didn’t seem to mind, though.

“Isn’t she amazing?” Celia asked the audience at the end. “Connie Benson!” I couldn't tell whether Celia had been trying to humiliate her, or not. But Celia ran over to Connie after the set.

“Man,” my flatmate Caitlin marvelled. “What do you think she is like in person?”

“I’ve met her a few times,” I said. “I think what you see is what you get.”

That weekend, Celia turned up at our flatwarming in the Valley with a small entourage at around midnight. Her friend Marcus apologised on her behalf as they arrived. “You know Celia,” he said. “She wanted to make an entrance.”

Marcus apologised on her behalf. “You know Celia,” he said. “She wanted to make an entrance.”

“Doesn’t matter,” I smiled. “Come as you are, whenever you like.”

It was a great night. Celia insulted the music, the lighting, and everyone at the party straightaway.

“What is this?” Celia’s head swiveled. “You’re living in some student flat?”

My flatmate tried to tell her a joke. Celia didn’t let her finish. “I’ve got a joke!” she declared. Then she forgot the ending, and cracked herself up anyway.

Caitlin stared. “I’m laughing. Your joke is really funny.”

“Cunt!” Celia crowed.

Caitlin put an arm on her shoulder. “Celia. I’m glad you’re here. But this is my house…”

Celia had already moved onto the record player. I tried to apologise for Celia, but Caitlin didn’t care. “Oh, I think she decided I was all right in the end.”

“What is this music?” Celia cried. My flatmates had put on something… electronic. “Change it!” she hollered.

I was more hesitant. “Someone wanted to hear this…”

“Put something that you like on,” Celia insisted. “You have good taste.”

She had no knowledge of my taste, but was charming enough to get people to go along in spite of how little what was said stacked up against facts.

At one point she sallied up next to me as I messed around on the organ in our hall. “That’s really good,” she encouraged, her eyes locked onto mine.

Immediately after I put on some rock and roll, a boy started dancing in our lounge with a broom.

Celia smiled. “See?” She cranked up the volume.

“We have to keep it down,” my flatmate Icky insisted. “Noise control already came. I don’t want my stereo taken away.”

“The neighbours only called noise control because of that shithouse music you were playing before,” Celia insisted. “They didn’t like the BASS. It has to do with FREQUENCY. This is a higher frequency, it’s fine.” She cranked the volume back up on her way out to the backyard.

Icky stared after her. “I think I’m in love.” He turned it back down once she had left.

“This lighting is awful,” Celia mused. “Lighting can make or break a party.” We turned a few lights off. “Better,” she insisted.

“She wasn’t that bad,” my flatmate Jenny said later on. “She wasn’t causing drama for the sake of it. Everything she was saying was about trying to make the party better.”

Celia was still putting records on when I slithered off to bed around two in the morning. The next day my flatmates told me that she was one of the last to leave.

Our time together was so short when compared with those who loved her and spent decades by her side. Yet as her spirit drifts from the bottom of the South Island to the top of the North Island and flies out over Cape Reinga, it feels still like I ought to share the little that I knew. If there was a legacy to carry forwards from the short time I spent with Celia, it was to engage. Celia can be channeled any time someone moves with a certain modus operandi: Pay no mind to precedents. Focus on making the music good. Improve the party.

I have been lucky enough to find something in New Zealand, though I can’t quite yet describe it. If all of the people who had an impact on each other’s lives all over these islands could be seen at once, it would light up the night like rich constellations in a cloudless winter sky. But as time passes, clouds are forming. The brightest lights are slowly fading, and some are disappearing altogether from sight.

Yesterday, another soft glowing star faded from the constellations that tell the story of a time and a place.

Go well, Celia.